Effects of Running with Turn Shorts

Shorted-turns in the field winding can cause operating conditions which may limit unit loads. If conditions are extreme, forced outages may occur.

The effects include:

Rotor vibration that varies with field current changes (thermal sensitivity and/or magnetic unbalance).

Higher field current is required than previously experienced at a specific load.

Higher field currents result in higher operating temperature.

Higher operating temperatures make additional turn short development more likely. A vicious cycle of turn short development often causes a rapid increase in shorts.

Decreased power generating efficiency.

See below for additional explanations:

1. Rotor Vibration that varies with field current changes (thermal sensitivity and/or magnetic unbalance).

A. Coils with turn shorts operate at lower temperatures than coils without shorts.

This is because the heat produced by a coil is a product of the heat/turn times the number of active turns in the coil. For example, a coil with one short out of 10 total turns (9 active turns) will produce 90% of the heat of the same coil on the opposite pole with no shorts (10 active turns). The difference in heat production can cause a temperature gradient to develop across the rotor body. The pole with the short will run cooler and expand less than opposite pole , producing a rotor bow in the direction of the hotter running pole (i.e., opposite the pole with the short). The resulting rotor bow will produce a Once/Revolution vibration.

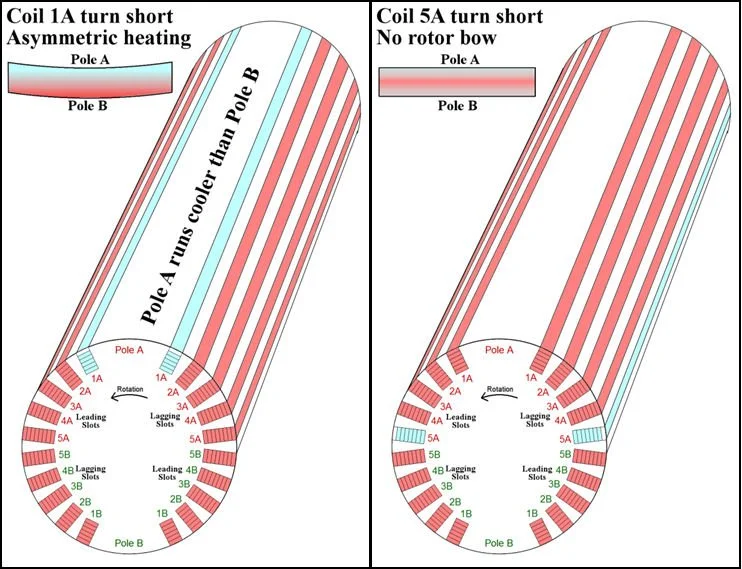

The magnitude of the temperature-gradient will be a function of the percentage of turns being bypassed and the location of the affected coils. Shorts in the smaller coils (Coils 1, 2 and 3) have a much larger impact than shorts in the largest rotor coils. This is because the location of the slots serving Coils 1, 2 and 3 lie closer to the pole faces, so shorts in one of these coils produces a strong temperature gradient (Coil 1A short image). On the other hand, shorts in the largest rotor coils have their cooler running slots close to 180-degrees apart and that geometry will not produce a significant temperature gradient across the rotor body (Coil 5A short image).

The rotor bow resulting from a given temperature depends upon the rotor stiffness. Longer and thinner rotors will be more susceptible to bowing.

The changes in vibration after field excitation change have a long time lag since the thermal mass of the rotor prevents quick temperature changes within the rotor body. The larger the rotor, the longer the time lag.

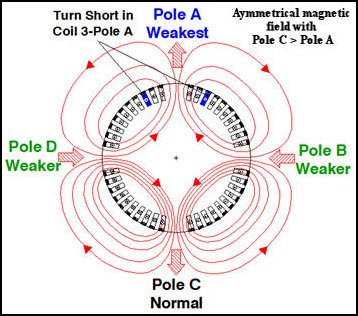

B. Shorted-turns in four-pole rotors will cause unbalanced magnetic forces.

Shorted turns in two-pole rotors do not generally cause an unbalanced magnetic force since the symmetry of the magnetic field is not greatly disturbed unless the rotor has a severe turn short condition involving the small coils on one pole. For example, we have seen magnetic unbalance in two-pole rotors that had a coil-to-coil short bypassing all the turns in two adjacent smaller coils. However, turn short induced vibration issues for two-pole rotors are almost always due to a temperature-gradient induced rotor bow (see above).

For four-pole rotors, vibration issues due to turn shorts is mostly due to magnetic field asymmetry, although temperature-gradient induced rotor bows will add to the vibration caused by the magnetic field asymmetry. The pole with the short will produce a weaker magnetic field than the opposite pole and will pull on the stator core less strongly. This will produce a Once/Revolution vibration issue that directly affects both rotor and stator core vibration.

Changes in vibration due to magnetic asymmetry track instantaneously with changes in field current. Vibration can be classified as due to magnetic asymmetry or temperature-gradient induced rotor bow by how fast the vibration changes with field current.

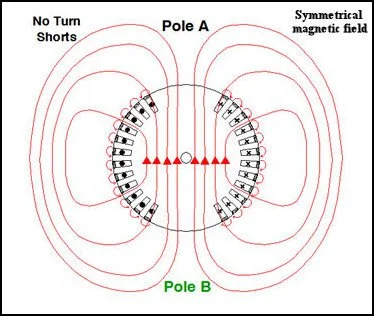

Figure 2B - Two-Pole Rotor with a Coil 3A turn short

The Coil 3A short initially reduces the magnetic field around rotor, but the symmetry of field is not greatly perturbed. The magnetic field strength of the rotor will quickly be restored by the Automatic Voltage Regulator (AVR). The AVR will increase field current until the stator voltage is returned to the set point.

Magnetic asymmetry in two-pole rotors is not normally significant enough to cause rotor vibration unless the shorted turn condition is severe and affecting the smaller coils on one pole.

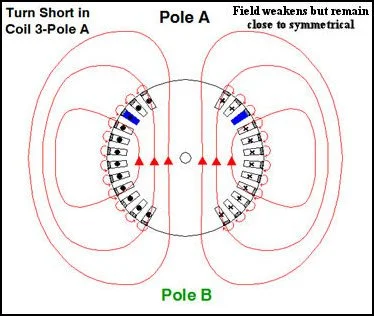

Figure 2C - Four-Pole rotor with no turn shorts

With no shorts, the magnetic field around rotor dure to the field current is symmetric, with flux exiting the two North Poles (A and C) and entering the two South Poles (B and D). Flux from each pole is shared with the two adjacent poles.

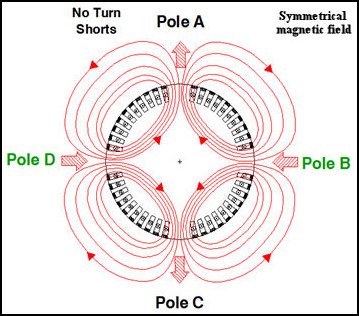

Figure 2D - Four-Pole Rotor with Coil 3A Turn Short

The Coil 3A short produce a magnetic field asymmetry, with Pole A’s field being weaker than Pole C. Pole C will pull on the stator core stronger than Pole A, producing a Once/Revolution vibration directly affecting both the rotor and the stator body. The vibration will change instantaneously with changes in field current.

2. Higher field current is required than previously experienced at a specific load.

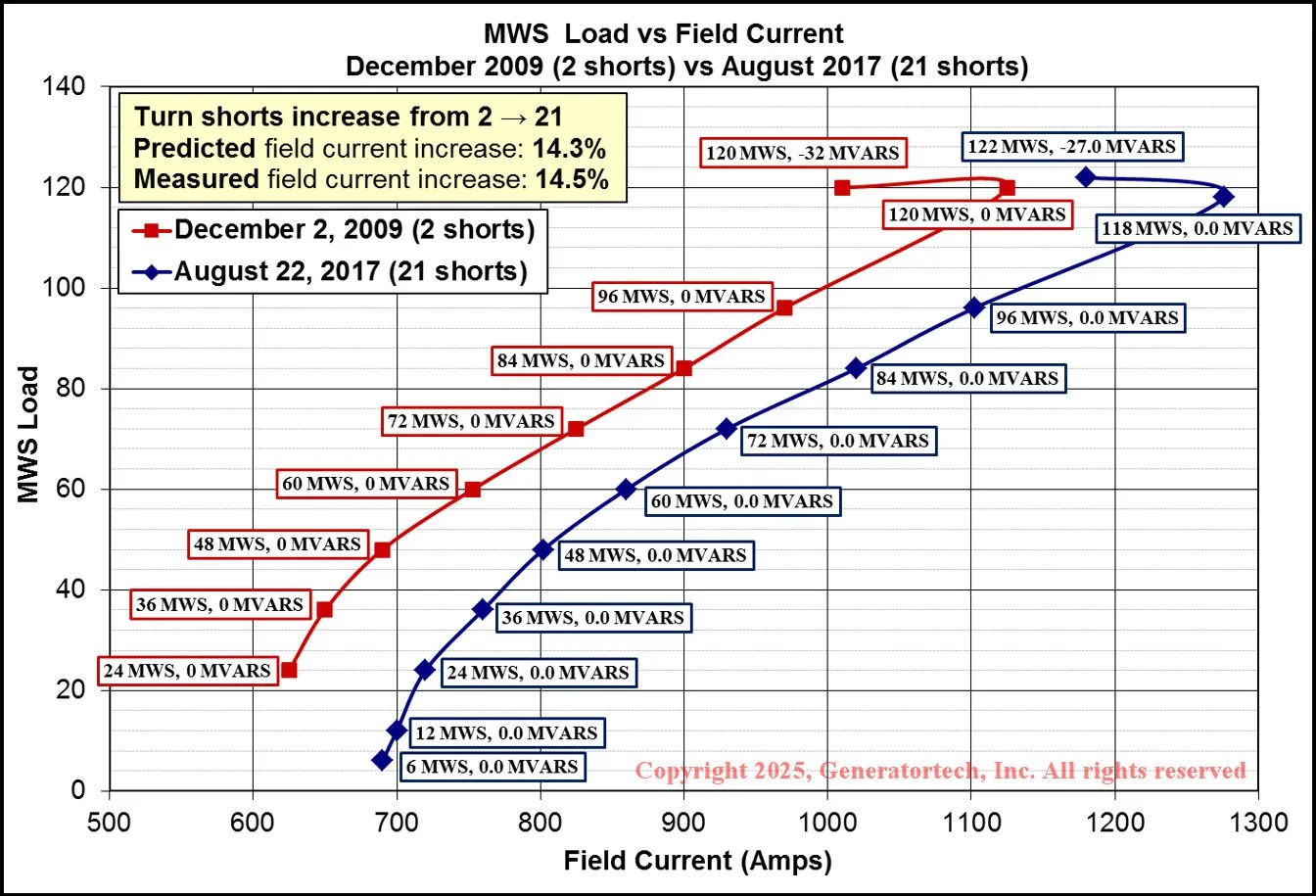

When turn shorts occur, higher field current is required to maintain a specific load. This is because more current is needed to maintain a given rotor magnetic field with fewer active turns in the winding (i.e., to maintain the same Amp-Turns value).

Exciter capacity may limit unit load if greater than 5-10% of the field winding is shorted out.

The chart shows data from two tests on a 134 MVA generator, whose turn shorts increased from 2 to 21 shorts. The measured field current increased averaged 14.5%, tracking very close to the predicted value of 14.3%.

The increase in field current will also increase the heat produced by each active turn, leading to higher operating temperatures for the rotor winding.

3. Higher field currents result in higher operating temperatures.

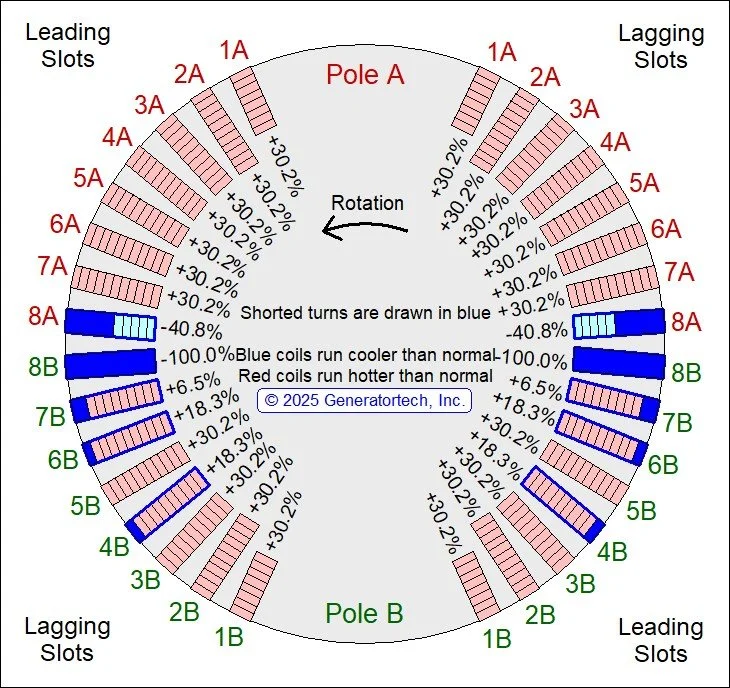

The higher field currents resulting from turn shorts increase the heat produced by each active turn (heat is proportional to the square of the current). As the temperature of the turns increases, copper resistance will grow larger and this will increase heat production even further.

The rotor cross-section shows the same 134 MVA generator discussed in (2) above, with 21 turn shorts involving a partial coil-to-coil short between Coil 8A and Coil 8B. The percent increase in heat produced over normal is displayed for each rotor coil. The very large jump in required field current produced at least a 30.2% increase in heat production in coils with no turn shorts. The resulting temperature increase caused the turns to expand more than normal, which produced conditions that favored additional turn short development.

4. Vicious Cycle of Turn Short Development

The higher rotor winding temperatures caused by turn shorts creates conditions making additional shorts more likely to develop. Once a critical number of shorts has developed in a winding, the number of shorts will continue to rise quickly. Only a rotor repair can prevent this vicious cycle from causing a unit outage.

The example shows a large 680 MVA generator that ran for at least 5 years with 1 to 2 shorts. However, in the next 1 1/2 years, the rotor developed 8 new shorts (10 total shorts in nine separate coils). When the rotor had 10 total shorts, each active turn was producing at least 25.2% more heat than normal. This was a runaway condition that would not have stopped at 10 total shorts, however, a successfully rotor rewind produced a short free rotor winding.

The rotor cross-section shows an animation of the turn short locations detected in the test. Note some interesting vibration issues resulting from the symmetry of turn short locations. For example, a large vibration issue caused when the rotor had a single short in Coil 1A was eliminated when a symmetrical short developed in Coil 1B. A similar situation occurred when the rotor had 10 total shorts - the symmetry of those shorts did not produce a significant vibration problem. The clearing and redevelopment of the short in Coil 1B is not uncommon.

Animation of the Turn Shorts Over Time and the corresponding rotor cross-sections shows the locations of the turn shorts detected during each test before the rotor rewind. When the Coil 1B short first developed, it eliminated the vibration due to the Coil 1A short. The Coil 1B short cleared and re-developed. Note how the symmetry of turn short patterns strongly affects vibration.

5. Decreased power generating efficiency.

The increase in field current and cooling requirements over what would be required to produce the same amount of energy with a rotor with no shorted turns will reduce the overall power generating efficiency of the unit.